Specifications

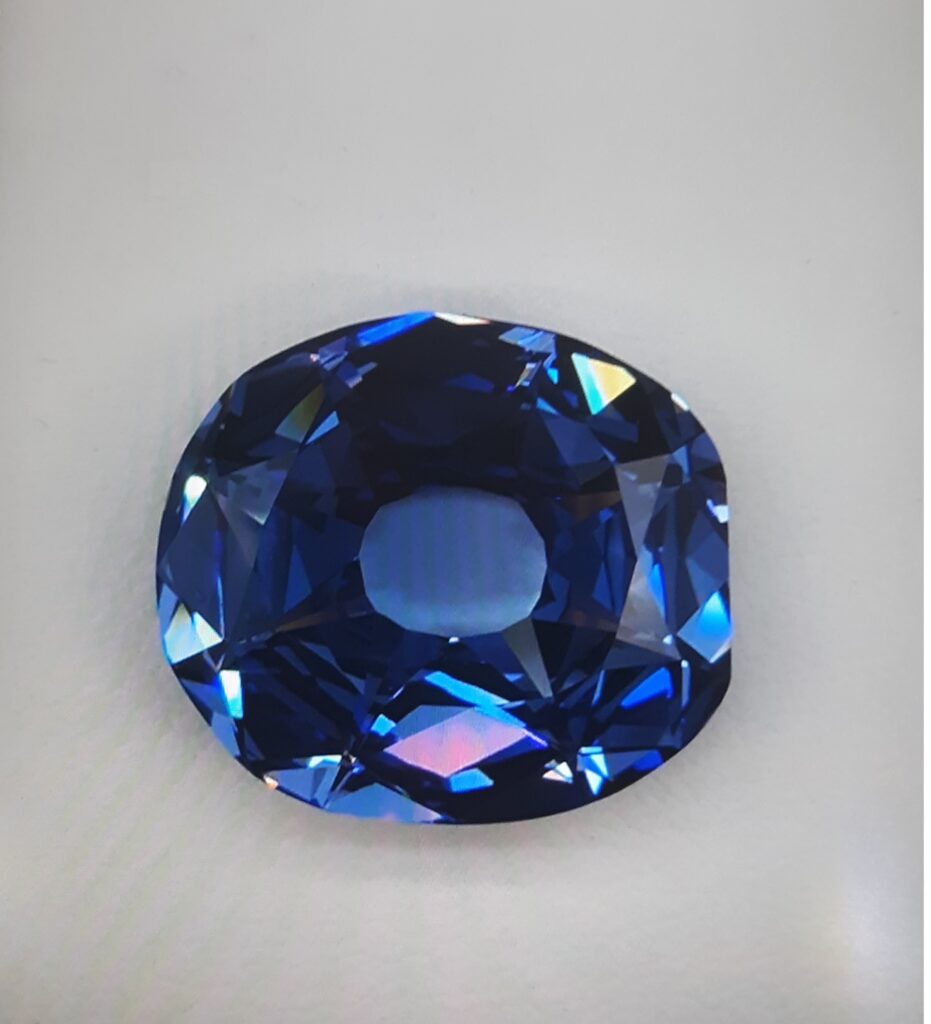

Weight: 35.56 carats

Dimensions: 24.40 x 21.46 x 8.29 mm

Color: Light Blue

Weight of Rough: Unknown

Origin: India

Date Found: Early 1600’s

Current Location: Private Ownership

Details

Requiem for the Wittelsbach

The Wittelsbach diamond is one if those rare diamonds that has survived the ravages of time and history. Probably discovered in India in the early 1600’s, its cut shows that it was exported and cut in Europe probably around 1650. Its documented history started in 1664 when King Philip IV of Spain gave it to his 15-year-old daughter when she became engaged to the Emperor Leopold I of Austria. It passed through many owners, then disappeared in the early part of the 20th century.

In 1962, Joseph Komkommer, a Belgian diamond cutter, was asked by a customer to “improve” a diamond cut in a very antique style. The owner wanted it recut to more modern standards. Fortunately, Mr. Komkommer realized that it was the Wittelsbach, lost for several decades, and recommended that it not be touched. He eventually formed a consortium and purchased the stone.

Fast forward to 2008. Christie’s sold the Wittelsbach to the owner of a very prestigious jewelry firm of impeccable credentials on Dec. 10. Those with a love of large or famous diamonds were now curious as to what was to be done with the stone. The new owner shortly thereafter went public stating that it was to be recut to remove surface damage, improve the brilliance, and perhaps darken the stone by two shades to dramatically increase its value, all done at a cost of an estimated four carats.

Should the stone be recut?

The Wittelsbach’s cut has been described as a stellar brilliant, so named due to the radiating pattern of facets around the culet. This makes the Wittelsbach one of the earliest examples of a brilliant cut. Interestingly, high-resolution photos taken by Christie’s shows that the cut is outstanding. The facet meets are nearly perfect, even under ~30X magnification. Due to the perfection of cut, it may be the earliest example of magnification being used for diamond cutting. Tool marks on the stones surface may provide clues as to procedures and techniques used to create such a masterpiece.

So, what will really be lost, other than an estimated four carats of diamond?

Asked another way: What was lost when the conquistadors destroyed the codices of the Mayan civilization? Or when the millions of papyrus scrolls burned in the great library at Alexandria? How about the destruction by the Taliban of the two Buddhas in Afghanistan, or the hundreds of Rodin sculptures lost when the Twin Towers fell?

Civilizations have come and gone, and we all survive just fine without any of these great works. But what have we lost?

In the case of the Wittelsbach, what’s at stake is at minimum over 350 years of history, as every nick, chip, and scratch has a story to tell. Just because we can’t decipher these stories doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

The new owner certainly has the legal right to do whatever he wants to do with the stone; after all, he paid over $27 million for it. But doesn’t he also have the moral obligation to protect what he has acquired?

Once recut, the Wittelsbach will no longer be the Wittelsbach; it will become “the diamond formerly known as the Wittelsbach.” I believe that relegating it to a mere piece of rough that needed to be manipulated is a gross insult to the skill of the unknown cutter. It is also an insult to the rest of us, as a piece of world culture will be destroyed for the sake of commercialization. This will be a willful act, not an accident, and in the scheme of world history, no different than the willful destruction of the codices or the Buddhas — it’s just a different altar being worshipped upon.

The Florentine, Pasha, Nassak, Koh-i-Noor, and other famous diamonds have fallen to the “modern” scaife. Must the Wittelsbach also?

April 2010

Well, Laurence Graff has done it, he has recut the Wittelsbach. It now weighs a bit over 31 carats, and is called the Wittelsbach-Graff diamond. In a way, I’m glad it was renamed, as the perpetrator of this vandalism is at least proud enough to put his name to the act he committed.

What is really wrong with this recutting, other than the issues mentioned above? Let’s look at the motivation. Francois Graff has stated “If you discovered a Leonardo da Vinci with a tear in it and covered in mud, you would want to repair it. Wehave similarly cleaned up the diamond and repaired damage caused overthe years.” I don’t know how long Francois has been married, but I’m reveling in over three decades. Imagine what I would go through if I “suggested” to my wife that perhaps she needs to get her crows feet taken care of, perhaps dye her hair back to brown instead of the salt-and-pepper it is, or rediscover that 18 year old body.

It actually goes deeper than this, and summed up by Gabi Tolkowsky (the best diamond cutter of our time) so succinctly as “the end of culture”. The diamond WAS the diamond, for better or worse, but whatever it was, it was at least honest. Gemologically speaking, the recut stone is a better color and has improved clarity (i.e. worth more). But again, what has been lost other than 350 years of history that cannot EVER be recovered?

Graff has certainly answered what is more important to him- money or history. Reveiw the facts and create your own opinion, but if you love famous diamonds and the story they tell, your worst conclusion should be “Who cares?”